Wing Chun’s Secret Weapon – the Fook Sao

The following is an excerpt from Sifu Jason’s new book, “Wing Chun’s Foundation: Siu Lim Tao.”

The Fook Sao section is the slowest, not just in Siu Lim Tao, but of any of the Wing Chun forms. It’s importance is accentuated by this very fact and we do well to consider it carefully. Not only is it the slowest section, it’s also the most eccentric looking thing you’re going to do in Wing Chun. Period. Having your hand cupped weirdly in front of you and moving it with painful slowness along the center line has to be the most un-combat looking thing a person can do in a combat system. So, what’s the deal with it and why is it so important?

There are two primary things to know. First, it’s teaching us to attack and defend the center of mass. Second, it’s teaching us the fundamentals of close-quarter contact or, in another way of saying it, street-fight clinching.

The aspect of defending and attacking the center of mass is something akin to making sure your gun is loaded before a gunfight. The modern martial art world is so shot through with hysterical and illogical support of MMA that it simply doesn’t occur to most of us that the easiest way to truly injure someone is by hitting them in the throat. Sure, there’s the occasional joke about a throat-punch here and there but no one practices it and even less than that, no one practices defending it.

This isn’t to say that we hope to see broken windpipes in the octagon soon. No, of course not. What we’re saying is that in a situation where it’s life or death, with someone much larger and stronger, such attacks are critical. The Fook Sao structure, is therefore, the key to being able to achieve real self-defense skill. To have a self-defense system that eschews the attack and defense of the body’s weakest link is the height of folly.

To be clear, sparring and drills of that nature are very beneficial for one’s accuracy and timing. That’s certainly true, but they can give one a dreadful false confidence. In real-fighting, the sort of thing Wing Chun is concerned with, it’s necessary to attack and defend the softest, most vulnerable targets. And that’s exactly where Fook Sao comes in.

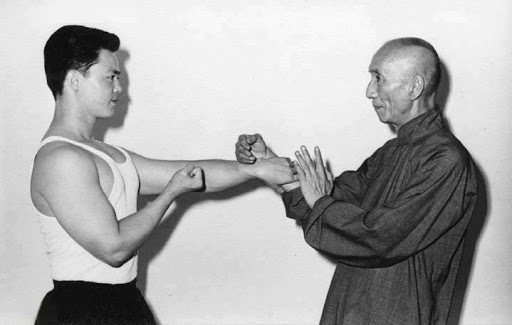

The key to it is the elbow position. If the elbow flares out, the structural support is broken and the enemy will be able to break through your guard. It should be known, in light of this statement, that a good Wing Chun fighter, properly trained and educated in the reality of fighting, is nearly impossible to grapple with due to their ability to seize the throat of the enemy whenever they (the enemy) vacate the center in order to grab (as seen in the photo above). Misapprehension of the core principle of Fook Sao is catastrophic to your Wing Chun. There is no “hand-chasing” or “baby-sitting the hands” in Wing Chun! Attack and simultaneously defend your center mass and vulnerable targets. You don’t care about the centerline as an abstraction. You care about the targets and center of gravity the centerline protects. The centerline isn’t a thing; it’s a reference to those things.

If Fook Sao isn’t chasing hands then what is it chasing? It’s “chasing center” or “chasing critical targets.” In this way, by learning how to properly occupy and control the centerline (in reference to these targets) one becomes a formidable self-defender. The throat/neck, jaw, and eyes, as well as one’s balance (by pushing, pulling and shoving) are constantly attacked with fast, springy power developed by the Fook Sao section.

The other aspect of this section that’s exigent is the ability to clinch/bridge properly. Unfortunately in fighting we aren’t always able to hit the target we want. Sometimes things aren’t going our way. There are two ways that one can deal with, that is to say, shut down the offense of the enemy in a helter-skelter environment. One is to be mobile and use evasion. The other is to tie them up. This is, incidentally, why grappling methods work quite well at times. It’s the tie-up that keeps the grappler from getting hit if they do it properly. The thing is, Wing Chun people often don’t understand this connection with grappling methods. A BJJ fighter that is able to grab his enemy is able to nullify their striking. You see this also in boxing when fighters use the clinch.

Well, the Fook Sao represents any top or outside hand. Tan Sao represents the structure you need if you have an inside hand relative to your opponent. In other words, Wing Chun clinches, ties up their hands (or bridge) to gain control of the enemy so they can’t strike. Fook and Tan, amongst other things, but chiefly, are types of clinching positions. Wing Chun has been nearly ruined because people don’t understand this and use chi-sao as a game of “Gotcha” or some hyper-technical arm wrestling match. No! A thousand times, no! We bridge. We tie them up! We use these logical and fundamentally sound structures to shut down the offense of the enemy and launch our own attacks. This section is the gateway to understanding close-quarter fighting.

This aspect of fighting, clinch control and striking the body’s most vulnerable targets, is virtually unknown today. I’d go so far as to say that the systematic training of this is utterly absent from modern fighting arts. The closest we get is the clinch in Muay Thai, boxing and grappling systems. The methods of those arts differ but they all use variations of the clinch to control the offense and balance of the enemy. Wing Chun, you should know, seeks to achieve the same thing yet with the critical difference of using close-range striking to the throat, neck, jaw and eyes. To leave these targets – both the attack and defense of them – out of Wing Chun is to eviscerate the system. In order to achieve this objective, though, we must master the Fook Sao principle and structure, which mean we must master Siu Lim Tao.

Get My Free Pass

Fighting Speed!

Was Bruce Lee fast?

That’s like asking if the Avengers franchise made any money.

Or if the sun is hot.

Anyway, with all the bickering and disagreement in the JKD/Wing Chun world, one thing everyone can agree on was that Lee was exceptionally quick. He was so fast, in fact, that it seems hard to imagine him being so popular without all that speed. But, more to our point, the very system of JKD is built on – and absolutely requires – a fair degree of speed. I’ve said before that the system is built around the stop-hit, which is to say, counter-attacking, and you can’t do that if you’re too slow. That would be like an ugly model, or a clumsy dancer…or an honest politician. Slow JKD is a contradiction in terms.

Now, you might think that speed is an essential quality in any fighting art but that’s actually not true. Speed will help, of course, but it’s far from the dominant attribute of, say, BJJ. JKD, on the other hand, rests upon the foundation of quickness and without it the whole structure comes tumbling down.

But what kind of speed are we talking about here? And how do we train for it?

First, we must have the right technical/tactical structure of the ready position, footwork, and straight, non-telegraphic strikes – preferably from the forward side. Each of these three technical points integrate without contradiction into the tactical framework of what JKD aspires to do – stop-hit the bad guy! Lee was obviously gifted with good genes for movement speed, but he understood how important it was to not waste movement and/or have a bad plan of attack.

If there was a secret to the whole thing it was Lee’s understanding of the importance of foot-speed. Most people treat footwork like an afterthought. In JKD, it’s the central thing. Always. Fighting is about moving and distance control. The man that controls the distance controls the fight. This being the case, he worked assiduously on foot-speed both in technique training (footwork) and physical conditioning. He favored footwork that was cat-like and efficient. And by all accounts, Lee didn’t jog – he ran! Fast. Like he was getting shot at. Up hills. And he rode a stationary bike full speed too – with the resistance as high as it would go. Oh, and you may have seen photos of him on a trampoline. He used that for more power and explosiveness. All of this translated into an amazing level of movement speed. Thus, the first big secret to his speed was in his legs.

You see, Lee knew something about fighting that most people simply ignore: good footwork can and will beat every attack. It’s a basic but painfully true fact that if you can cover ground faster than your opponent, you have a significant advantage. And this was Lee’s goal with all of that conditioning. In JKD, we preach the “four hits” – hit first, hit straight, hit hard, hit often. Without foot-speed, you aren’t going to hit first because you’re at the mercy of the other guy’s movement. Being first is the heart and soul of JKD philosophy and training because action is always faster than reaction.

If you take a look at the vast majority of fighters, they move around, or they fire their techniques. Rare is the fighter that uses footwork as part of their technique. One such fighter was Roy Jones Jr. In his heyday, Roy was always boxing from the fighting measure – too far from his opponent to be reached without footwork. In fact, he used distance like a JKD fighter would – as his primary means of defense. He’d counter-attack expertly from the rim and he’d attack with lightning quick shots when his opponent wasn’t set, darting in and then shooting back out (or angling offline). He never hung out inside the pocket, awaiting a receipt, so to speak. Yet, while everyone was amazed at how fast Roy’s hands were – and sure they were blazing fast! – it was his explosive footwork that carried him expertly in and out of range. He was so good at this that one time, against a poor fellow named Richard Hall, he actually ended up behind the guy at one point. For a terrible moment, Hall actually didn’t know where Jones was! He did this, lest you forget, against another professional – a man paid to fight!

Add to this that Lee favored straight hits for JKD. Many fighters lose their discipline under pressure and use round-house type punches and kicks. But the straighter the strike, the more direct it is, the faster it is. More still, you can throw combinations better and the straight hits integrate into your footwork/ready-position mix too, allowing you to move and adjust distance with an incredible rapidity.

But there’s something else. Movement speed is only one part of the equation. A fighter must have good timing too. To be fast in fighting is to be fast “on-time”. Simple movement speed is superfluous if an action is executed at the wrong moment. In fact, timing can be said to be the most crucial element in all of combat because nothing – literally nothing – works without it. Lee understood this and meticulously added timing drills to JKD training. One example is the Jab-to-Jab drill. There are several variations of this essential drill but the most basic one is for you and a partner to stand opposite a heavy bag. One partner initiates an attack with their jab and the other tries to counter-jab as fast as they can. While the reacting partner is getting the best work in during this drill, both parties actually benefit. The initiator must be cognizant of their pacing, not falling into a predictable rhythm. And, above all else, he must not telegraph his strike. Of course, the counter-puncher is trying to beat his partner to the punch. You can add difficulty by having the initiator step back so they have to use footwork with their attack. You can also allow the starter to fake too! Lastly, the counter-attacker can use different counters like the side-kick or cross to the body.

Pop-ups on the mitts work wonderfully too. Have a trainer “pop” a line (like a jab or kick) and hit the target as fast as you can. The unpredictability is key.

So, in all, remember that a fast punch or kick is nearly useless without footwork and timing. With them, though, you have a nearly unbeatable combination of qualities because speed kills – your opponent if you have it, or you if you don’t.

Happy training.

Get My Free Pass

JKD’s Most Important Technique

It’s probably surprising to hear that something so (allegedly) basic as the Ready Position is JKD’s most important technique. I understand, I really do. But we need to deal with this because not understanding the primacy of JKD’s On-Guard is the central mistake infecting Lee’s fighting method. Seriously.

First, let’s cover why it’s so important.

To begin, the Ready-Position is ready to do two primary things: hit and move. Specifically, it’s ready to fire non-telegraphic straight BOMBS, preferably from the lead hand/foot. Assuredly, the rear-side gets in on the action but only as a coup-de-grace. The supremacy of straight hits is a critical aspect of JKD that we shouldn’t take for granted. Unfortunately, too many people do. The JKD Bi-Jong is the launching pad from which the primary weapons (lead punch, side kick and snap/hook kick are thrown). Any significant departure from this set-up will invariably degrade the efficiency, power and speed of these weapons.

Next, the Ready-Position is ready to move. It’s easy to confuse movement with footwork. Any fool can move; JKD fighters move their Ready-Position by means of specific footwork designed especially for this purpose. If, for example, you bounce when moving, instead of shuffling as you should, you obliterate your ability to instantly fire when needed. First, you have to stop bouncing, then reset, and then fire. This literally destroys your JKD because now you can’t instantly counter-attack. Your options then are to try and avoid everything by running or getting into a brawl.

In this, one can see the careful integration of the three technical fundamentals of JKD: the Bi-Jong, JKD/fencing style footwork to transport the on-guard, and the pulverizing straight hits. It’s a package deal. If one of these go, the others are soon to follow. And this is why you absolutely cannot, repeat cannot, simply add things willy-nilly to your game and call it JKD.

Roundhouse swings and bad footwork are generally added by the student because they haven’t been taught that keeping the on-guard position is of central concern. After all, if I lose focus on this, I’m liable to throw strikes that telegraph and/or make instant recovery impossible. The goal of the JKD fighter is, as Bruce called it, stillness in motion. That is to say, we want to fire without warning from the ready-position and then return immediately to it. That’s it! The more we deviate from this standard, the harder everything else becomes.

Constant drilling must be done in order to ensure that the JKD fighter is able to maintain their discipline under pressure. The Romans once had the greatest military on the planet. They called their practice maneuvers; their maneuvers were called bloodless battles; their battles were called bloody maneuvers.

If you’ve ever been to an amateur MMA or boxing event, you’ll notice how wild the fighters can get. Clearly, they know better than to swing so hard that they fall down if they miss, but novice fighters do this all the time. Why? Simple. They haven’t yet developed the discipline required to control themselves under pressure. This is no small point. Pressure causes us to make mistakes, so the JKD fighter must train and train and train – not until they get it right but until they have to try to do it wrong!

With all this said, it shouldn’t surprise you that Bruce Lee said that all JKD practice was the practice of the ready-position. The fighter that’s always ready to hit (hard!) is a dangerous fighter. And the JKD tactical mind-set is to “get off first” – to stop-hit or counter. Even the attacks in JKD are actually “early” counters because the enemy is off balance or, for whatever reason, unprepared. Everything in JKD swirls in orbit around the interception/stop principle and this simply can’t be achieved without the integration of the technical fundamentals of the on-guard, footwork, and straight bombs.

So, why do so many people mess this up? Well, there are numerous reasons but let’s focus on two big ones.

First, people erroneously think that JKD’s governing philosophy is relativistic, which is to say that anything goes and there are no fixed principles. But if you say there aren’t any fixed truths, you just said one. Get it? By saying there are no absolutes, you’re saying one. We can avoid all this confusion by properly understanding what it means to “have no way as way.” This should be understood – primarily – from a tactical standpoint. Feints, draws, traps, counters, changes of timing, angle, etc. These are all the when and why of fighting. The technical structure of JKD, though, isn’t able to be varied much at all (though it can, of course, be tweaked for practical purposes) for the very reason that human anatomy is a rather fixed thing.

If I drive someplace, I’m bound by certain specifics. What kind of car do I have? What’s the speed limit? What kind of law enforcement is there? (Remember George Carlin’s number one rule of driving: if the police didn’t see it, I didn’t do it). What are the traffic conditions? You see, we’re “bound” by certain things but also tactically free to adjust. If there’s a traffic jam on my primary route, I can take another highway. I can leave earlier or later to avoid congestion. What I can’t do is mount a missile launcher on my roof and blast my way to work – tempting though that is.

Naturally, we are free to do whatever we want, but we aren’t free from the consequences.

Which leads us to the second error – complexity. The scourge of complexity happens because we fail to properly identify the facts of reality. The JKD on-guard/straight hitting/footwork combination allows us to best control distance, avoid being a good target while simultaneously attacking the softest targets of our enemy. And this isn’t going to be easy because the other guy is trying to hurt us. He’s going hard and fast and he’s moving. This necessitates ruthless efficiency. Any complicated movements that don’t achieve simultaneous evasion and counter should be jettisoned. We endeavor to keep it simple because the stakes are high and the other guy won’t cooperate.

In all, there’s no way to simplify fighting if you’re out of position and can’t counter-attack. This is why the JKD bi-jong is absolutely the most important technique because without it, nothing else works.

Get My Free Pass

Soft Targets: The Achilles Heel of Sport Based Fighting Systems

It seems rude to point out, almost like bringing attention to the finely dressed woman at the party, replete with the best fashions, that she has something stuck between her teeth. But the vast majority of martial systems today are suffering from a glaring weakness. And, lest you think that by vast majority I am merely throwing words around, and the problem isn’t all that bad, be certain that 99 in 100 martial artists are suffering from this. And this may even be a generous, soft-peddling of the problem.

The problem, for the most part, is that martial arts have gone the way of martial sports. Some have eschewed the primacy of attacking and defending the body’s weakest areas for the idiotic sake of complexity too – they just think other stuff is more cool, which is like a man getting attacked in an alley by a gang and whipping out his trusty nunchucks instead of a Glock 9MM because the aforementioned rice-beaters are way cooler. Such is the insanity of a man throwing a reverse kick rather than an eye-jab.

It’s these twin terrors that have utterly decimated modern martial arts from being what a martial art was and is meant to be: a fighting system, instead of a cool martial athletic club. And that’s exactly what most schools are because they’re focusing on things that aren’t essential to all-out fighting. What is? Well, for goodness sake, it’s scientifically attacking and defending the softies – the eyes, throat, groin, shins and knees.

Now listen, I’m sure this is going to offend many out there because we all have our favorites, but this isn’t about a match in a ring or a cage or even a sparring match at the school on any given Wednesday night. This is about survival, pure and simple. If two thugs attack you, helter-skelter ambush style, throwing haymakers and looking to do serious damage and then stomp your head into the pavement after they knock you down, and you’re fighting with rules then you have a serious oversight impeding your success. And, remember, success and failure in this instance could very well mean life or death. So, I’m terribly sorry to have to throw some methods under the bus, but in the name of the truth and your safety, these things need to be considered.

The Attribute Paradox

A person’s physical size, strength, movement speed, timing, endurance, flexibility and pain tolerance all play huge roles in their success as a fighter. Don’t ever believe otherwise. As JKD students we should train intensely as if these were the only qualities determining whether or not we live or die while at the same time developing tactics and techniques that reduce our dependence on attributes as much as possible.

The reason for this seeming contradiction is simple: if we fight in such a way that requires us to be the better athlete in the fight and, for whatever reason we are not, then we have horrible problems. Conversely, if we ignore physical conditioning and tell ourselves that we’re going to just kick a dude in the nuts and be done with it, and we miss, or he eats the shot and keeps fighting, then we’ve created another grave conundrum for ourselves. Both are needed. The proof of this is in the body and work of Bruce Lee himself. He trained like a professional fighter, was a superlative athlete, and yet ruthlessly attacked the key areas of the enemy. JKD reconciles these two – attributes and real fighting tactics so as not to be overconfident and/or unprepared in either area. To my knowledge, no other fighting method does this quite so well, with so much logic.

For example, it can easily be argued that some of the finest conditioned athletes on the planet – some of the physically toughest – are modern MMA fighters. I can personally attest to their grit, determination and skill. Owning a martial arts school with MMA fighters in it, I routinely get a chance to see some of these fighters up close and personal and I marvel at their pursuit of excellence and devotion. Boxers and kickboxers too…they are outstanding athletic warriors and we should be encouraged by them – us martial artists – to train hard and be in the best condition we can.

But there have been many examples in the cage where one fighter “accidentally” pokes his opponent in the eye. (We must note that some fighters have this happen too many times for it not to be an intentional act on their part, but that is another story). Nevertheless, whenever a wayward finger jabs an eye there is always a terrific response. The recipient howls in pain, covers his eye with his hands and hops around like a toddler in pain. Yes! A great and world-class fighter reduced to this by a finger in the eye. Naturally, this causes a break in the action too – giving the stricken fighter a chance to recover himself. This same scene happened as long ago as the first Ali-Frazier fight in March of 1971 when the ref accidentally poked Frazier in the eye as he endeavored to break up a clinch. Frazier, who had taken hundreds of sharp blows to the head from Ali all night, unfazed, was quickly hopping and howling after the middle-aged refs finger caught him.

The same happens when low blows land in both MMA and boxing matches as well. You see, no matter how well conditioned these fighters are, there is literally no way to toughen one’s eyes or village people. There just isn’t. It’s not possible. You can marvel at a Muay Thai fighter kicking a tree with his shin bone all you want but know this: his guys are open before and after every kick. Bruce Lee saw this and we should too. And this is precisely why there are no Muay Thai round kicks dominating real JKD practice. Again, it goes back to trading in your handgun for an Okinawan farm tool. Why waste all that time getting good at something not as effective? It makes no sense unless you’re ego driven and want to wow people with all that power. Or, you just love throwing the round kick like that, which is fine as long as you know that it isn’t the most practical means of defending yourself.

At this point there’s bound to be the dissenter that will bellow on about how some champion or another can round kick a house in half. Well, this very well might be true but the truly valid question as to self-defense is whether or not you can do that. In either event, maybe your Thai idol can truly kick that hard but one has to conclude that kicking a man in the groin is always better than kicking him so hard that you could knock his house down. All else being equal, no man’s thigh is less prepared for a strike than his fellas. Moreover, and this mustn’t be forgotten – in throwing the roundhouse kick we have to expose our own groin. But throwing a good groin kick yourself can keep you maximally covered.

Thus, it logically and ruthlessly targets the eyes, throat, groin, shins and knees, while using footwork and timing to protect their own targets. If the JKD fighter, properly trained, discovers during the encounter that they are indeed the better athlete, so much the easier for them, but they never assume such a thing. One groin strike can incapacitate a fellow, maybe even kill him. Most methods today don’t even bother defending this. It’s like the Death Star floating along with a big red-spot on its exterior, virtually undefended. Certainly, since its so wide-open and hardly defended, one doesn’t have to use the Force to attack it.

So, no, we’re not saying that a JKD student should avoid the vigorous work of training like a fighter. He should. We should strive to be in better shape than sport fighters, in fact. Our founder – that ridiculously ripped fellow in all the movies that inspired us – was. We should be like him and get in the best shape we can be in. But, also, we need to train like this while avoiding becoming a sport fighter. We’ll cover this more as we go and it has everything to do with the right attitude (starting here) and the ready position, footwork and weaponry integration that only JKD offers the modern warrior. This way, in the end, we can hang with the sport fighters in terms of conditioning, timing and emotional toughness, but we are eye-jabbing, groin kicking machines. Lee was a professional; his JKD followers of the current generation should be too. But he was a warrior, not a sport fighter and we must remember that as well or else JKD becomes diluted and unfit for the realities of real world violence – life and death, not victory or defeat; and not unanimous decision or split decision, but safety or morgue.