Defense Wins!! Learn How To Not Get Hit

You can’t lose a fight if you can’t get hit. This is why defense is the key to self-defense. Most schools miss this and focus on offense too much, but if we can’t shut down their attack it doesn’t matter how good our punches and kicks are.

All fighting is a clash of speed and power. So, what happens if you’re the smaller or (gasp!) even slower fighter in an altercation? For many, such would be a nightmare scenario, but it need not be if you’re well versed in logically sound defensive tactics.

Now, before we get started, let’s be honest.

Very few martial artists seriously contemplate and train with the idea of being outgunned in a fight. That’s a serious problem and shows how a form of ego takes over one’s self-defense training. Yes, we should be training to get stronger and faster, but no matter how hard you work, you still might not be the best athlete in a fight. That’s the thing about self-defense: we don’t get to choose our opponent. They choose us! Ego isn’t our amigo; we should be training to stop the other guy’s attack. This is unpopular due to the delusion of pride that infects many schools, but many times you don’t have to “win” the fight (insofar as sport rules are concerned). You merely need to not lose.

And that requires defense. Again, no matter how you look at it, if they can’t hit you, they can’t beat you. Good defense is the key for self-defense because that’s something that doesn’t demand that you’re bigger than your foe.

A few years ago, a Wing Chun friend of mine was watching some of my students train evasiveness (head movement, parrying and footwork), and he looked as if he’d just eaten something foul. “Are you kidding me?” he protested. “Why don’t they just step inside and cut the guy off, take his position, and blast him out of there?” He demonstrated what he meant, and it all looked wonderful, except he was leaving out some critical detail in his tactical analysis: He was well over 6’5 and around 240lbs. Of muscle. Rumor has it that he bench presses small family cars.

Naturally, this fella has rarely experienced the awful reality of being the smaller and weaker party in a fight or sparring match.

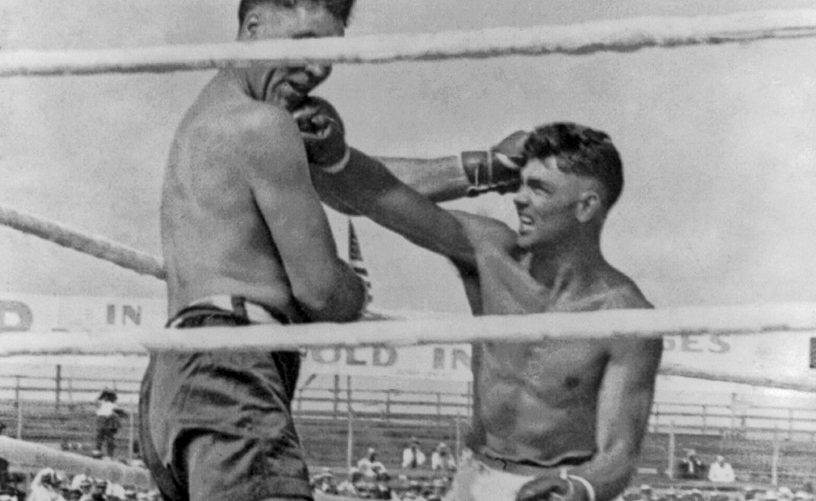

In trying to simplify, which is the art of narrowing down things to their foundational principles, we must avoid oversimplification, which is the omission of relevant detail. This well-intentioned Wing Chun man was guilty of this. He just couldn’t conceive of a world, where he wasn’t the big dog in the fight. It’s an easy error to make, but a potentially deadly one. The old Boxing adage is true: When a good big man hits a good little fella clean, the good little guy goes bye-bye. That’s why there are weight classes in Boxing and MMA.

A good example of this was Mike Tyson. We don’t think about this often, but Tyson was a small heavyweight, often giving up several inches in critical height and reach. This being the case, vintage Tyson spent the vast majority of his training time on being elusive. Yes!

“Iron Mike” Tyson, at his best, was a defensive wizard.

He trained head movement, head movement, and more head movement.

His brilliant original trainer, Cus D’Amato, had a basic rule for him: Move your head before and after every punch. This was steeped in the old boxing adage that if you don’t move your noggin, your opponent will move it for you!

When Tyson was Tyson—a dynamic and wondrous machine of destruction— he was virtually impossible to hit. When he stopped being so elusive, however, and charged straight into the pocket, his effectiveness plummeted.

So, as you can see, developing footwork and head movement can prove invaluable, because if you have the upper body movement of a heavy bag, you better be able to take as much damage, too. And it isn’t about fighting defensively. It’s about being smart. It’s about being elusively aggressive.

If your instructor is a great athlete and no one in the school can compete with him, that’s nice and inspirational and all that. Sure. Good for him. But what does that do for you? Self-defense isn’t a spectator sport. It’s about what you can do and your super-athlete instructor or Sifu isn’t going to fight for you. Nor are you able to fight like him. This is precisely why a truly logical self-defense school places a premium on counter-attack, evasiveness, and defense. Always.

Anyone who takes a precursory glance at Bruce Lee in action can tell he was greatly influenced by these truths. Many who worked with him spoke, not only of his almost preternatural speed and power, but also of the near impossibility of hitting him with a clean shot when sparring. Lee knew that swapping blows with big men, when he was only 130ish pounds or so, was a recipe for disaster.

If you’re new to the world of head movement and evasion, start with a mirror to learn good form. There are three ways to move your head and evade a punch. First, you can change the angle by moving your upper body, so your chin is in line with your knee. This keeps your head at the same level, but changes the line and is called “Slipping“. Next, you can change your level by “Ducking” straight downward. This is achieved by bending the knees and moving straight down. Allow your waist to “bow” just a little naturally as you duck. As always, your chin does not pass your knee-line (with the duck, the imaginary line between your knees), or you’ll be off balance. Last, you can also change level and angle by “Bobbing“.

With the bob, you’re doing an angled duck, and that’s what a bob really is—a fancy duck. Again, don’t let your chin go past your knee. A “Weave” is simply a sliding motion to change your angle from one knee line to the other.

Head movement is really upper body movement. As the shoulders slide, turn or drop, they carry the head out of the way of a blow. Calling it head movement is really a misnomer, as you can see, because if the head moves without the body, something truly bad has happened. Yeah…you’re probably dead. I’m not a doctor, but our body and head generally need to stay connected.

Once you have the hang of this, by practicing in front of the mirror, move on to having a partner gently toss punches at you. Keep it simple and slow until you get the hang of it and then add footwork.

Ultimately, good head movement should be lightning quick and smooth. Get back to your ready position as soon as you can so you can counter attack.

Last, at the advanced stages, get in the ring with a boxer and have them throw punches at you (wear appropriate protective gear) and focus on evasion and defense. Many of my Wing Chun students do this and focus on not getting hit, while they work for a clinch, which is exactly where they want to fight…inside. The thing is, getting inside, without getting KO’d, is harder than many people think. Either way, though, having a great defense is a tremendously valuable asset for any fighter. If your primary game is “long,” then use the evasiveness tactics to snipe with jabs, eye-jabs, groin and knee kicks.

Remember, no matter how tough your enemy is, he can’t do what’s physically impossible: He can’t hit what’s not there. And being aggressive doesn’t mean being reckless.

Get My Free Pass

JKD & Boxing

The True and Practical Origins of JKD

Excerpt from the upcoming book, “JKD Infighting”

For all the hand-wringing and overly philosophical meanderings about what JKD is or is not, let’s get this out in the open. Let’s not meander and make a big deal out of what should be patently obvious to one and all – as obvious as the day of the week. Bruce Lee’s JKD is a self-defense/martial art offshoot of old-school boxing. His foundation was Wing Chun and he saw that as a practical system of combat but for two reasons he adapted a more boxing framework to his JKD.

First, he couldn’t finish his Wing Chun training. When Lee left Hong Kong in late 1958 he left behind the Ip Man school. Ip Man’s approach to teaching, we should note, was very much based on practicality. He encouraged his pupils to test the theories and training for themselves rather than blindly taking his word for it. This was – especially for a Chinese fighting method in the 1950’s where loyalty to the Sifu was paramount – a radical thing. I contend that it was this that was the central aspect of the Ip Man school and gave rise to men like Lee as well as his senior, Wong Shun Leung (who was also responsible for Lee’s training under Ip Man).

At that time in Wing Chun history, the method wasn’t considered a classical art. Ip Man was an upstart in the Hong Kong community. He’d been chased out of mainland China by Mao’s forces and left without his family and forced to scratch out a living in a city still recovering from the ravages of Japanese occupation in WW2. During that period from December of 1941 thru August 1945 food had been so scarce that hundreds of thousands perished. When the occupation began there were nearly 2 million people in Hong Kong. By the time they left there were only 700,000. It was a time that’s hard to imagine for the modern westerner when one of the greatest health threats facing the impoverished in America is obesity! In Hong Kong at that time, the people were literally starving to death. Please keep that in mind when you see old photos of that era.

At any rate, we can understand the toughness of a people who’ve survived such a war and such horrific deprivations. And it was to these survivors – men like Wong Shun Leung – that Ip Man broke from tradition and told to go test the stuff to see if it worked.

Which brings us to the second reason that Lee moved toward boxing in his later years.

Quite simply, in America, which had been, by comparison, untouched by the ravages of war, and was awash in material wealth, there wasn’t a culture of “trying things out” in the martial community like there had been back in Hong Kong. But driven by the philosophy of Ip Man, that being that a theory had to work in practice, Lee was hell-bent on practicality. Boxing offered this to him. It gave him the ability to test things out and, not only that, but a rich history of adaptation and change. In short, to Lee’s mind, boxing was the logical extension or, perhaps more accurately, the martial sibling to his foundation art of Wing Chun.

The proof of this is a letter that he sent to his senior and mentor in Wing Chun, Wong Shun Leung. Here’s the letter:

“Dear Shun-Leung, Jan. 11, 1970

“It has been a long time since I last wrote to you. How are you? Alan Shaw’s letter from Canada asks me to lend you my 8mm film. I’m sorry about that. It is because I have lost it when I moved my home. That film is already very old and I seldom use it, so I have lost it. I am sorry for it.

“Now I have bought a home in Bel-Air. It is about half an acre. There are many trees. It has the taste of a range. It is located on a hilltop near Beverly Hills. Moreover, besides my son Brandon, I have had a daughter, Shannon, who is seven months old now. Have you re-married? Please send my regard to your sisters. Recently, I have organized a film company. I have also written a story ‘The Silent Flute’. James Coburn and I will act in it. Stirling Silliphant is the screen-play writer. He is a famous screen-play writer (In the Heat of the Night). We plan to make the first fighting film in Hollywood. The prospect is good. About six months later, the filming work will begin. All who participate in this film are my followers. In the future, Steve McQueen may also work together with me.

“I am very excited about this plan. As to martial arts, I still practice daily. I meet my students and friends twice a week. No matter they are western boxer, Tae Kwon Do learner or wrestler, I will meet them as long as they are friendly and will not get angry.

“Since I started to practice realistically in 1966 (Protectors, gloves, etc.), I feel that I had many prejudices before, and they are wrong. So I change the name of the gist of my study to Jeet-kune-do. Jeet-kune-do is only a name. The most important thing is to avoid having bias in the training. Of course, I run everyday, I practice my instruments (punch, kick, throw, etc.). I have to raise the basic conditions daily.

“Although the principle of boxing is important, practicality is even more important. I thank you and Master for teaching me the ways of Wing Chun in Hong Kong. Actually, I have to thank you for leading me to walk on a practical road. Especially in the States, there are western boxers, I often practice with them too. There are many so-called masters in Wing Chun here, I really hope that they will not be so blind to fight with those western boxers may make a trip to Hong Kong. I hope that you will live in the same place.

“We are intimate friends, we need to meet more and chat about our past days. That will be a lot of fun? When you see Master Yip, please send my regard to him. Happiness be with you!

“Bruce Lee.”

When we couple this letter with the fact that Lee’s Tao of Jeet Kune Do, published posthumously and originally intended to be a manual for his personal students, was actually copied itself from old boxing and fencing manuals, we have settled the issue of JKD’s origins. Our contention that Lee’s JKD followed the principles of boxing and that he owed this to his instruction in Wing Chun from Ip Man isn’t speculation but, rather, the direct words and deeds of the man himself. In the famed Tao, often seen as evidence of Lee’s martial genius, he literally copied dozens of pages from old boxing and fencing manuals. Modern boxing had grown out of the fencing era, relying on straight hits, footwork, timing and deception. So, indeed, he was a genius but a different one than most of us are led to believe.

The infighting presented in this book, therefore, will have a greater streak of boxing running through it than the JKD Foundations book. At long range, JKD can resemble fencing a bit more but that’s all gone when you are fighting in the trenches. A thing to note, of course, is Lee’s own words in the letter to his mentor. He says that though boxing principles are important, practicality and realism are the key. What this means is that Lee built his JKD on the well vetted and tested principles of boxing. Modifications made for street-fighting – such as takedown defense, head-butting, eye jabs, low blows, etc. – while necessary and extremely helpful in the cause of personal defense, are still in orbit around the boxing principles. Those principles are what Lee liked to call aliveness. In particular, they’re evasion, powerful striking from any angle, and mobility.

If you were so inclined to say that JKD is simply boxing then, we would disagree. There’s a difference in building on the foundation of a thing and being that thing. A boxer can cheat but he would have to make a conscious effort to override his muscle and tactical memory in order to do so. The JKD approach is a scientific “cheating” – a highly organized, yet simple adaptation of the boxing methodology in order to help keep the self-defender as safe as possible in the event of a sudden and violent encounter. Thus, JKD is like boxing but isn’t boxing. On the other hand, those JKD variants that are less like boxing and more like something else – like say, Kali – are less like JKD too. To jettison the boxing roots of JKD – especially on the inside – is to cut oneself off from the scientific nature of the combat.

To prove my point, I’d like to offer this example.

Back in 1996 my school was very small. I had a 400 square foot place on Wade Hampton Boulevard in Taylors, South Carolina. (Talk about humble beginnings…the Lord has blessed my work mightily!). One evening a guy came in and asked why I wasn’t teaching BJJ. He went on to explain that unless I was teaching Gracie style BJJ that I’d be out of business in short order. The strength of his argument rested upon the small sample-size evidence of the recent UFC matches in which Royce Gracie was dominant.

Well, to this I replied that boxing was still the king in any universe where people throw punches at each other. As soon as the fighters adapted their tactics to account for BJJ – that is, learned to sprawl and punch properly, you’d see a radical reordering of the UFC. He laughed derisively at that and shook his head in a way a man shakes his head when someone tells him he was once abducted by aliens. Or that 9/11 was an inside job. Or that you can trust Congress.

Anyway, here we are over 20 years later and we know that a UFC fighter without boxing is an accident waiting to happen.

We must add, though, that the old-school boxing we present – and that being Jack Dempsey style predominantly – is better suited for all-out fighting than MMA. This is due to the variables like asphalt rather than mats, headbutts, eye, throat and groin strikes, multiple opponents and so on. We’ll cover all this in more detail as we go but we remember that Lee’s goal was realism and that he once remarked that boxing was “over-daring” due to its reliance on rules. It was his belief that a martial artist was training for war, not sport and that sport, while extremely helpful in regard to testing certain aspects of one’s game, if left unchecked, would dominate one’s understanding of self-defense and thus weaken it. We remind the reader that if you aren’t cheating in combat you aren’t trying to win insofar as we define cheating as the use of tactics and targets that are the most difficult to defend.

In closing, if you think that Dempsey or Tyson were destructive, and they certainly were, then you need to understand how and why that was the case. That’s what made Lee such an outstanding thinker. He saw people getting the results he wanted and began his research there. JKD infighting is, therefore, the extrapolations of close-quarter boxing applied to street-defense – all-out, life-or-death combat.