JKD’s Genius: Attack the Weakest Targets

A SERIOUS MISTAKE IN ALL-OUT FIGHTING, ONE THAT BRUCE LEE PREACHED AGAINST AD INFINITUM, WAS LEAVING YOUR “SOFT TARGETS” OPEN AND, JUST AS BAD, NOT SYSTEMATICALLY ATTACKING THOSE AREAS— ESPECIALLY THE GROIN.

If you’re training for real-world self-defence, you should ask yourself if there is a primary and foundational emphasis upon attacking and defending this vital soft spot. If there’s not, then you have to ask the basic question: why not? Why would any enterprising individual forced to defend themselves, facing grave injury or death, not whack the bad guy in the village people? This question is especially pertinent to Jeet Kune Do practitioners who are supposed to be practising a science of self-defence, and what’s more scientific in combat than striking the enemy’s weakest target?

We aren’t practicing a self-defense science if we aren’t systematically attacking and defending the body’s weakest targets.

Across the modern self-defense landscape, there’s talk about simplicity and directness, yet there’s precious little whacking bad guys where it hurts the most. Back in Bruce Lee’s day, when Karate stylists stood in a closed-off stance, it was somewhat more difficult to get at that particular target— hence the point of that stance, after all.

However, nowadays, with the proliferation of sport fighting, there’s rarely any regard toward defending against groin attacks. Yep, it’s open season, if you’re so inclined.

The UFC, incidentally, is a highlight reel of how damaging groin kicks can be, and yet these are always accidental. Moreover, these wayward groin kicks are scored by a bare foot rather than a shoe, boot or sneaker.

As tough and well conditioned as these fighters are, when even an errant toe smacks them in their nether regions they are greatly reduced. Think about this for a second—some of the world’s most well-conditioned combat athletes are rendered defenceless by errant, rather than intended, strikes to their groin. And did I mention these combat athletes are wearing groin protection?

Well, if this doesn’t embolden you to become a real ball-buster (sorry, couldn’t help myself), then you aren’t paying attention to real world violence. One look at how much damage to “fair” targets some of these fighters can take should warn you off of throwing your primary strikes at well-padded areas. Your life might depend on this, right? Right?!

Well, stop messing around with sport tactics and get focused on attacking your enemy’s weakest targets. It’s the whole Death Star/Luke Skywalker thing, really, except that the bulls-eye isn’t so difficult to get at. And the dude won’t actually blow up (though one can always hope).

The amazing thing about it is, the vast majority of trained fighters are oblivious to the unpleasant reality that a quick, powerful shot to the groin can take them out. Drop them…and leave them at the mercy of more damage, or allow your escape (whichever is contextually correct in that particular self-defense situation). Consequently, most modern martial artists/sports-trained fighters have no systematic attack and defence for this area. Bruce Lee often referred to Western Boxing as “over daring” for precisely this reason.

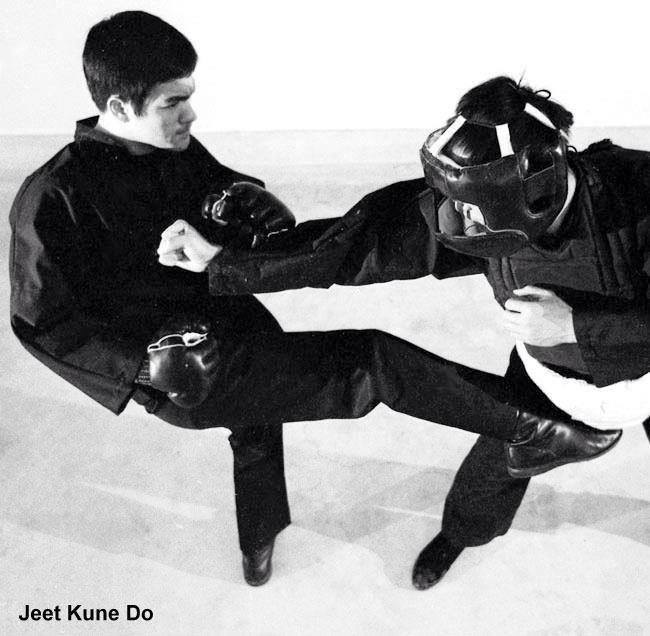

Anyway, with all that said, Jeet Kune Do is a perfect set-up for below the belt attacks and we do this from both long and close range. The entirety of Lee’s fighting method is set up to use the lead hand and foot to attack the enemy’s weakest targets, which, of course, implies an integration of the ready position, footwork, tactics and striking tools.

Jeet Kune Do is not, repeat not, a motley mash-up of disparate systems thrown together where you say, “Ah, yes … we can kick the chap in his fellas too,” while firing off round kicks with your nerve-deadened shin bone.

The thing is, all practice is the practice of some theory, and the Jeet Kune Do theory is to use footwork and timing to diffuse the bad guy’s offense while using straight, non-telegraphic hits at the most vulnerable targets. We aren’t interested in finding out if we’re the better athlete. We aren’t interested in some macho competition. This is about survival. If you really need to compete, take up golf. Or tennis. Or chess. This whole nonsense about, “let’s see who’s the better man” in regard to violence is a wee bit morally whacky. Isn’t the better man the one whose family adores and trusts him? Isn’t the better man the one who has raised others up and has a proven track record of productivity throughout life?

Because of nonsensical ego tripping, we forget what self-defense is all about. And because of that, we jettison the training of JKD as it should and ought to be.

The lead hand and leg of the Jeet Kune Do fighter are the dominant offensive tools. The snap kick, which is a straight version of the Jeet Kune Do hook kick, can pulverise the enemy’s low-line before he responds. Today’s fighters, as already mentioned, have lots of experience using leg checks against round kicks. However, the Jeet Kune Do snap kick, often thrown at the end of a hand combination for extra stealth, whips up off the floor and shoots right at the target of the guy in the open (facing) stance. In Jeet Kune Do, the rear foot slides forward to gain range and replaces the front foot, which immediately fires at the exposed groin line. After the explosive, whip-like kick, both feet return to their original position (the visual image is a pendulum). This leaves you out of your ready position for the least time possible, which is of vital importance because who knows…you might miss. Or maybe the guy’s a Cyborg sent from the future to kill Sarah Connor.

I digress.

Seriously, though, every weapon thrown in Jeet Kune Do meets the critical requirement of blending in and out of the ready position with the utmost ease-—this kick included. This allows you to fire a multitude of strikes, on the move if need be, all while leaving you as small a target as possible. What’s not to like?

Should the fight enter close range, you should still be focused on hitting the guy in his most vulnerable areas. Short body shots such as hooks and uppercuts are easily converted to groin attacks and should be used at every opportunity. By using a Paak Sau or Lan Sau, one can hold and hit too, which works tremendously well since it disrupts the enemy’s balance and takes at least one limb away for defence. A side note: low blows don’t necessarily need to hit the groin to easily double the guy over or drop him.)

The critical point is this: Jeet Kune Do, being a fight science, not a combat sport, has an integrated system of protecting one’s most vulnerable areas while viciously attacking those of the enemy. Many people make a mistake of thinking they can mix Jeet Kune Do with sport-based approaches. Training practices, yes; tactical/technical points, usually not. If the aim is stopping the threat expeditiously, then one absolutely must consider the systematic attacks Jeet Kune Do offers to such vulnerable, fight stopping areas like the groin. And, remember, if you’re in a fair fight, your tactics stink.

Get My Free Pass

Defense Wins!! Learn How To Not Get Hit

You can’t lose a fight if you can’t get hit. This is why defense is the key to self-defense. Most schools miss this and focus on offense too much, but if we can’t shut down their attack it doesn’t matter how good our punches and kicks are.

All fighting is a clash of speed and power. So, what happens if you’re the smaller or (gasp!) even slower fighter in an altercation? For many, such would be a nightmare scenario, but it need not be if you’re well versed in logically sound defensive tactics.

Now, before we get started, let’s be honest.

Very few martial artists seriously contemplate and train with the idea of being outgunned in a fight. That’s a serious problem and shows how a form of ego takes over one’s self-defense training. Yes, we should be training to get stronger and faster, but no matter how hard you work, you still might not be the best athlete in a fight. That’s the thing about self-defense: we don’t get to choose our opponent. They choose us! Ego isn’t our amigo; we should be training to stop the other guy’s attack. This is unpopular due to the delusion of pride that infects many schools, but many times you don’t have to “win” the fight (insofar as sport rules are concerned). You merely need to not lose.

And that requires defense. Again, no matter how you look at it, if they can’t hit you, they can’t beat you. Good defense is the key for self-defense because that’s something that doesn’t demand that you’re bigger than your foe.

A few years ago, a Wing Chun friend of mine was watching some of my students train evasiveness (head movement, parrying and footwork), and he looked as if he’d just eaten something foul. “Are you kidding me?” he protested. “Why don’t they just step inside and cut the guy off, take his position, and blast him out of there?” He demonstrated what he meant, and it all looked wonderful, except he was leaving out some critical detail in his tactical analysis: He was well over 6’5 and around 240lbs. Of muscle. Rumor has it that he bench presses small family cars.

Naturally, this fella has rarely experienced the awful reality of being the smaller and weaker party in a fight or sparring match.

In trying to simplify, which is the art of narrowing down things to their foundational principles, we must avoid oversimplification, which is the omission of relevant detail. This well-intentioned Wing Chun man was guilty of this. He just couldn’t conceive of a world, where he wasn’t the big dog in the fight. It’s an easy error to make, but a potentially deadly one. The old Boxing adage is true: When a good big man hits a good little fella clean, the good little guy goes bye-bye. That’s why there are weight classes in Boxing and MMA.

A good example of this was Mike Tyson. We don’t think about this often, but Tyson was a small heavyweight, often giving up several inches in critical height and reach. This being the case, vintage Tyson spent the vast majority of his training time on being elusive. Yes!

“Iron Mike” Tyson, at his best, was a defensive wizard.

He trained head movement, head movement, and more head movement.

His brilliant original trainer, Cus D’Amato, had a basic rule for him: Move your head before and after every punch. This was steeped in the old boxing adage that if you don’t move your noggin, your opponent will move it for you!

When Tyson was Tyson—a dynamic and wondrous machine of destruction— he was virtually impossible to hit. When he stopped being so elusive, however, and charged straight into the pocket, his effectiveness plummeted.

So, as you can see, developing footwork and head movement can prove invaluable, because if you have the upper body movement of a heavy bag, you better be able to take as much damage, too. And it isn’t about fighting defensively. It’s about being smart. It’s about being elusively aggressive.

If your instructor is a great athlete and no one in the school can compete with him, that’s nice and inspirational and all that. Sure. Good for him. But what does that do for you? Self-defense isn’t a spectator sport. It’s about what you can do and your super-athlete instructor or Sifu isn’t going to fight for you. Nor are you able to fight like him. This is precisely why a truly logical self-defense school places a premium on counter-attack, evasiveness, and defense. Always.

Anyone who takes a precursory glance at Bruce Lee in action can tell he was greatly influenced by these truths. Many who worked with him spoke, not only of his almost preternatural speed and power, but also of the near impossibility of hitting him with a clean shot when sparring. Lee knew that swapping blows with big men, when he was only 130ish pounds or so, was a recipe for disaster.

If you’re new to the world of head movement and evasion, start with a mirror to learn good form. There are three ways to move your head and evade a punch. First, you can change the angle by moving your upper body, so your chin is in line with your knee. This keeps your head at the same level, but changes the line and is called “Slipping“. Next, you can change your level by “Ducking” straight downward. This is achieved by bending the knees and moving straight down. Allow your waist to “bow” just a little naturally as you duck. As always, your chin does not pass your knee-line (with the duck, the imaginary line between your knees), or you’ll be off balance. Last, you can also change level and angle by “Bobbing“.

With the bob, you’re doing an angled duck, and that’s what a bob really is—a fancy duck. Again, don’t let your chin go past your knee. A “Weave” is simply a sliding motion to change your angle from one knee line to the other.

Head movement is really upper body movement. As the shoulders slide, turn or drop, they carry the head out of the way of a blow. Calling it head movement is really a misnomer, as you can see, because if the head moves without the body, something truly bad has happened. Yeah…you’re probably dead. I’m not a doctor, but our body and head generally need to stay connected.

Once you have the hang of this, by practicing in front of the mirror, move on to having a partner gently toss punches at you. Keep it simple and slow until you get the hang of it and then add footwork.

Ultimately, good head movement should be lightning quick and smooth. Get back to your ready position as soon as you can so you can counter attack.

Last, at the advanced stages, get in the ring with a boxer and have them throw punches at you (wear appropriate protective gear) and focus on evasion and defense. Many of my Wing Chun students do this and focus on not getting hit, while they work for a clinch, which is exactly where they want to fight…inside. The thing is, getting inside, without getting KO’d, is harder than many people think. Either way, though, having a great defense is a tremendously valuable asset for any fighter. If your primary game is “long,” then use the evasiveness tactics to snipe with jabs, eye-jabs, groin and knee kicks.

Remember, no matter how tough your enemy is, he can’t do what’s physically impossible: He can’t hit what’s not there. And being aggressive doesn’t mean being reckless.

Get My Free Pass

Use Your Head…as a Weapon!

Two things right off the bat.

First, when we say head-butt we don’t mean the imprudent and dangerous type you see in the movies. That’s a head-smash, which is a foolhardy and reckless means of using one’s melon. Literally smashing your brain-cage into anything is as bright an idea as trying to change someone’s mind on social media. And almost as dangerous. Don’t do it.

There was a singularly wise government plan in the 80’s to stop the use of illegal drugs. “Just say no.” It was, as all government ideas usually are, wildly successful and money well spent. Illegal drug use plummeted because people had never thought to just say no. Indeed, the land rejoiced and inner cities here in America became as peaceful and bucolic as a farm on a green Vermont hill.

Okay…well, that didn’t actually happen, of course. But they tried. Getting back to reality, and the issue at hand (or head), we’d like to co-opt that vacuous slogan and put it to good use. Just say no to the head-smash. A real head-butt has nothing to do with a head-smash. They’re like the difference between a skilled surgeon and Jack-the-Ripper. To be clear on the difference is to answer the usual objections to the head-butt by those who value their brain cells. They’re right. We do too. But we aren’t talking about the same thing because what they’re objecting to (rightly, we add) is the aforementioned head-smash. The real-deal is surgical. It’s a subtle and opportunistic action with huge upside.

And this brings us to the second point, which is that the recipient of an honest to goodness head-butt isn’t going to fare well. That’s more movie stuff, by the way. We see it all the time. There’s a fight and one of the guys winds up, pulling his head waaaay back, crossing time zones, and then BAM! The poor victim of the celluloid head-smash is taken aback, surely, but they’re always A-OK afterward and keep fighting. And not only do they keep at it, but there’s virtually no sign whatsoever that they just ate a hard skull moments ago. For all intents and purposes they may as well have done nothing more than sneeze.

Yeah, we all know that movies aren’t very good at depicting the reality of life, much less combat. Nevertheless, it’s quite easy to be influenced by them for the simple reason that we see it all the time. Movies and martial art demos are like porn for the self-defender. They fill our minds with woefully unrealistic expectations.

To that end we give you a few critical truths of one of the in-fighter’s greatest tools: the head-butt.

In reality, the actual head-butt is like a jab. A real head-butt is a quick smack with the top of your head. It’s an opportunistic thing and almost always done from the clinch, never from the outside.

Moreover, the target is the other guy’s face. As obvious as this seems it doesn’t go without saying. We should never use our forehead as a weapon nor should we target his.

A proper understanding of the in-fighter’s crouch and the scientific use of positioning cuts down on available targets for the enemy and opens up some for you. With careful practice you’ll gain a positional advantage on the inside through which you can hold-and-hit, especially to the lower abdomen and groin (great targets for short, but powerful punches), and menace the bad dude’s face with the top of your head. The head-butt is always done slightly upward and/or sideways, never down. The reason for this is all about the angle of contact. If the enemy is shorter, or is in a deeper crouch, the head-butt is off the table. Don’t take the shot. Moving downward to the target increases the risk of striking his forehead (or head) and that’s as much fun as a car crash. Seriously.

In Jeet Kune Do in-fighting the idea is to use the bridge/contact as a kind of “inside fighting measure.” In other words, the first order of business is to shut down the enemy’s offense. Some instructors illogically teach that you should be hitting all the time. But this neglects the defensive considerations necessary to stay safe. Grapplers and Muay Thai fighters use their respective clinches to smother the striking ability of their enemy and simultaneously set up their attack. Jeet Kune Do does the same thing. The difference is that in JKD we’re thinking of fighting without rules. It’s important to understand this point or else we’ll likely never have the opportunity to use this effective in-fighting tool. The JKD head-butt is a short-range weapon launched from a controlled in-fighting position that doesn’t compromise one’s defense or balance. It almost always requires some type of trap or clinch that momentarily immobilizes the enemy and leaves him unable to strike or grapple.

As with every other tool, the head-butt is used within its context and in combination with everything else. Footwork, trapping, pushing, striking, pivoting…it’s all in there even on the inside. Many of us, due to flawed presuppositions, get on the inside and illogically assume that everything stops. We’re grappling now, we tend to think. Or we think one-dimensionally. On the contrary, the skilled in-fighter is a whirlwind of combat science. By using the combination of paak-sao, laap-sao, lan-sao, angles, pivots, and careful positioning, the JKD in-fighter is able to fire brutal close-range combinations of dirty tactics. Low blows, head-butts, shin and ankle kicks…like a boxer’s one-two. Speed, power, control and lots of dirty, filthy stuff!

The best way to practice this is with a sparring partner you don’t like very much. Maybe he owes you money. Maybe he married the girl you wanted. Maybe he wears way too much Axe Body Spray.

No…but seriously…no matter how tempting all that might be, never spar with this stuff. So, how do we get good at it? Drills. Use the heavy bag to work on positioning and use the head-butt off of that. Never practice actually butting the bag, but put your head on the bag from your crouch position. To the uneducated it’ll look as though your using a short bob or duck, not an actual head-butt. Add light sparring drills to this where you work on bridging/tying up your partner in a non-contradictory manner, which is to say in a way that sets you up for good in-fighting.

It’s all about smart habits and reflexes developed through realistic but safe training. Now that’s using your head.

Get My Free Pass

Lessons from the Anthony-Metcalf Stabbing

Ego is the enemy.

It can get us killed. It can get us incarcerated for the rest of our lives too.

This is exactly the case with Karmelo Anthony and Austin Metcalf. The self-defense lessons are critical.

Seventeen year-old Karmelo Anthony stabbed 17 year-old Metcalf at a high school track meet in Texas on April 2. The life-altering issue that caused the conflict was Anthony sitting in the wrong section. And now one young man is dead, the other faces life in prison, and two families are ripped apart.

As it went, Metcalf told Anthony to move.

Anthony refused and reached into his bag and said, “touch me and see what happens.”

He had a knife.

Metcalf didn’t back down but insisted that Anthony move. In the end, Anthony stabbed Metcalf once in the chest and then fled the scene, leaving Metcalf to die there on that otherwise normal day.

We’ll let other people opine about and discuss the legality of Anthony’s claim of self-defense. What we’ll focus on is the fact that the altercation was so ridiculously avoidable. We’ll focus on the fact that all people – especially young men – must learn the principles of self-defense and abide by them.

First, all altercations have the potential to turn deadly. To risk escalation over something one isn’t willing to die for ahead of time is high folly. Therefore, always try and avoid and/or deescalate.

Second, nothing is ever gained by the use of violence. This doesn’t mean violence is wrong or that we should be pacifists. Clearly, a woman eye-gouging a rapist is morally correct in her action. But the “winner” in a self-defense situation gains nothing he/she didn’t already possess. If we applaud or approve of senseless violence, or define ourselves through it, we have serious issues of character.

Third, violence can only be used morally in the event of unavoidable threats to one’s safety. No other reason suffices for the use of force.

Fourth, in light of these truths, we must endeavor to leave the area if it becomes dangerous and/or try to alert the responsible authorities to the situation if you must stay. If Metcalf had simply left to get an authority figure, he might still be alive. If Anthony hadn’t refused to follow the rules of the meet and left the area he didn’t need to be in, he wouldn’t be facing life in prison.

If these principles had been applied, there would have been no fight. Metcalf was certainly correct that Anthony had no right to be where he was. That’s true. But in getting drawn into a confrontation that led to his death, he functionally died over a seat.

A seat in a public place he didn’t own.

Metcalf was right but what good does that do for him now that he’s dead?

Something so trivial became a life-or-death matter because the principles of self-defense were violated. (Again: we aren’t getting into the legal arguments of the case. Our focus is on the teachable aspect we should all take to heart.)

For self-defense purposes, Metcalf should have regarded Anthony’s demeanor and threat to “see what happens” – not to mention the possibility that he had a weapon – as reason to go get an authority figure.

A teacher. A police officer.

We must teach our young this basic principle because it can avoid tons of trouble.

For his part, Anthony could have avoided the whole thing by getting up and leaving. His overall behavior begs serious questions about his character regardless of whether a jury finds him guilty of murder. He illegally brought a knife to a school event, sat in a restricted area, and then refused to leave when challenged. These are all clear violations of the common sense principles of self-defense that establish and maintain peace in society.

Furthermore, you can’t use lethal force – morally or legally – over a “simple” altercation. To use deadly force one must be in reasonable danger of death or great bodily harm. Unless there’s some evidence we don’t know yet – such as Metcalf pulling a gun or his own knife, for example – there’s simply no legal or moral justification for Anthony using lethal force. You can’t shoot someone who shoved you. Self-defense must be proportional to the threat it means to stop.

It looks very much like ego was a contributing factor to the altercation itself and then, due to Anthony having a deadly weapon, it escalated into a death. The law of self-defense teaches us that though conflicts in life are sadly inevitable, it’s each person’s responsibility to seek peace and only respond with violence to actual or inevitable violence.

For example, I can’t punch a dude in a Dodgers hat because I regard Los Angelas fans as insufferable knuckleheads whose team spends obscene amounts of money for players. Again: we can only use violence to stop imminent harm.

Young men need to be taught these basic and critical principles. Running one’s mouth and saying truculent things to a potential enemy has landed many a professing self-defender in jail. Telling someone, “I’ll kill you if you touch me,” is a far cry different from saying, “please leave me alone.”

Ego, anger, and stubbornness are alive within all of us and that’s something a true martial art program teaches us to control. Again: we aren’t blaming Metcalf for getting stabbed. That deadly act is Anthony’s alone and he will have his day in court. But as self-defenders, we must learn the nature of the beast, so to say. We must remind ourselves of these truths and apply them to our personal lives.

Stay safe.

To check out Sifu Jason’s YouTube video on this:

Get My Free Pass

Simple, Not Easy

I once asked Ted Wong what he thought was the greatest obstacle in teaching JKD. Without hesitation he replied, “having to repeat yourself.” What he meant was that most of us are always trying to learn a new trick or some special secret instead of mastering the basics and keeping the main thing the main thing. We all have this tendency to major in minors, don’t we? Just look at the diet industry. We spend billions buying products to help us get thin when it’s rather clear that we need to put the hamburger down and go for a jog. But it’s always easier to eat the cookie…and then another. That’s the rule of life. Simple doesn’t mean easy; it takes great discipline to stay focused.

Moreover, by not keeping things simple – that is, applying the basics to life – we find that an increasingly stressful “complexity creep” sets in. The rule is: hyper complex systems are always downstream of bureaucracy and bureaucracy is the result of people forgetting what the main goal is. Focus on a derivative point instead of the primary thing and we find ourselves buried under a thousand illogical burdens. Ever work at a big company? Or at the biggest – the government? They’re classic examples of complexity creep swallowing up simplicity.

In that case, working in a bureaucratic nightmare, stress might kill you. Yeah…but under the pressure of a violent assault complexity can and will literally kill you. The genius of Bruce Lee was that he had the courage to not only understand this but he resisted all attempts to complicate matters. Since his passing, and despite the much appreciated work of Ted Wong, his protege, JKD has often fallen prey to the exertions of martial bureaucrats. Something catches their fancy…something draws their attention rather than the simple goal of keeping oneself as safe as possible in an unavoidable violent encounter and here comes that regrettable avalanche of complexity. And confusion.

JKD shouldn’t be confusing. It’s simple but not easy and the key to understanding its application is actually hiding in plain sight. Where? Well, in the very name – jeet kune do, which means, of course, the way of the intercepting fist. Now that should clear up some confusion right away as to what the intent of the system was/is and keep us from running down a multitude of rabbit holes.

So, what’s in the name? Well, for starters the word “jeet” generally comes into English meaning to intercept. From this we derive the idea of stopping or cutting off an attack with one of our own. When people ask me what JKD is I bring them to the name to illustrate its foundational purpose. Countering an attack scientifically has the great and underappreciated value of diminishing one’s risk of the reverse: running into a shot yourself. So many knockouts happen because the attacker ran into a strike he/she didn’t see because, well, it’s impossible to keep everything covered when attacking. To diminish this great risk, the counter-attack is indispensable. In fact, the all-time boxing great, Peerless Jim Driscoll, devoted an entire chapter of his book, The Straight Left, solely to the stop-hit.

In real world fighting, people don’t stand still. Watch the average demo on YouTube and you’ll see the other guy pause while Sifu Fantastic does his super-duper-awesome stuff. Lee called this dissecting a corpse. Real people keep firing back, often swinging wildly with haymakers and hooks. If one of those connects – goodnight. Bruce Lee understood this and realized the danger of complex motions in fights and instead relied heavily on the interception tactics to keep himself from getting unceremoniously KO’d by some knuckle-dragger’s haymaker. The best defense, of course, is a good offense and the best offensive tactic is to meet an on-rushing attack with a well-timed counter-attack, thus borrowing great force from the attacker. There’s tremendous shock value in getting the bad guy to run into a counter-strike. More on this later.

So, basically, this is the main goal of Bruce Lee’s JKD – to use counter/interception tactics against attacks.

Straight hits like the lead punch, eye-jab, side kick, or straight kick, best facilitate the intercepting concept and leave the JKD fighter with less exposure to danger than roundhouse strikes. Thus, JKD was built, like its parent arts of Wing Chun and old-school fencing influenced boxing, around straight hits. Take a look at Lee’s own work in the Fighting Method series. In one volume he covers ways to deal with different attacks. Take a look at the photos. An attack while walking down the road: low side kick. An attack while getting in your car: low side kick. An ambush from behind: low side kick. Ah! You can see a pattern here. The obvious being (besides the apparent danger of walking in a bad neighborhood while wearing sissy-white pants) that Lee preferred cutting off the attack with an attack instead of anything more complicated.

Now, some controversy comes in at this point from those that say such interception tactics won’t work for everyone because they aren’t as fast as Bruce Lee was. Their answer to this false dilemma is to insert other complicated techniques to solve the problem. It’s a false dilemma, though, because it leaves footwork and evasiveness out of the equation. Think of the intercepting kick or punch like a gun shot. If a man was running at you with a knife and you have a gun, and the distance was fairly close, it would certainly be to your benefit to move while firing. Likewise, if an attacker rushes you, the assumption is that you will likely have to move to avoid the attack. The genius of JKD is that like a gun, one can fire the straight lead punch while moving, hence achieving interception and defense simultaneously. There are other means of doing this, like slipping and hitting, or parrying and hitting, but the goal is always the same: avoid being a target and hitting back at the earliest possible moment. If you’re fast enough to nail him right away, great. Do it. If not, hit and move. Still simple.

This is quite literally why Lee coined his method the way of the intercepting fist – the straight punch and/or eye-jab are the only weapons one can consistently fire while on the move. A hook or cross or some other tool can only be thrown once with movement and then the fighter has to reset. The straight punch, though, demands no considerable disruption of balance so the JKD fighter can fire multiple shots while in transit and/or until the attack ceases or another good target (groin or shin/knee come to mind) becomes available. Lee didn’t call the straight punch the backbone of JKD for nothing. The whole of the system is a set-up for it. An opponent that runs into a heavy counter lead punch – delivered by a bare fist – makes himself decidedly less good looking in short order. That’s why the bare knuckle fighters of old leaned slightly back in their stance. Getting punched by a bare fist is slightly less pleasant than trying to find a parking spot at the mall during Christmas season (which leads to wanting to punch people in the face, but that’s another article).

This was the simple truth that Lee built JKD around – this is the rock and the foundation in which everything else is in orbit. The intercepting straight punch or kick, from the JKD on-guard, supported by footwork, slipping, parrying, and the other weapons when applicable. It’s simple, yes, but not easy.

Get My Free Pass

JKD & Boxing

The True and Practical Origins of JKD

Excerpt from the upcoming book, “JKD Infighting”

For all the hand-wringing and overly philosophical meanderings about what JKD is or is not, let’s get this out in the open. Let’s not meander and make a big deal out of what should be patently obvious to one and all – as obvious as the day of the week. Bruce Lee’s JKD is a self-defense/martial art offshoot of old-school boxing. His foundation was Wing Chun and he saw that as a practical system of combat but for two reasons he adapted a more boxing framework to his JKD.

First, he couldn’t finish his Wing Chun training. When Lee left Hong Kong in late 1958 he left behind the Ip Man school. Ip Man’s approach to teaching, we should note, was very much based on practicality. He encouraged his pupils to test the theories and training for themselves rather than blindly taking his word for it. This was – especially for a Chinese fighting method in the 1950’s where loyalty to the Sifu was paramount – a radical thing. I contend that it was this that was the central aspect of the Ip Man school and gave rise to men like Lee as well as his senior, Wong Shun Leung (who was also responsible for Lee’s training under Ip Man).

At that time in Wing Chun history, the method wasn’t considered a classical art. Ip Man was an upstart in the Hong Kong community. He’d been chased out of mainland China by Mao’s forces and left without his family and forced to scratch out a living in a city still recovering from the ravages of Japanese occupation in WW2. During that period from December of 1941 thru August 1945 food had been so scarce that hundreds of thousands perished. When the occupation began there were nearly 2 million people in Hong Kong. By the time they left there were only 700,000. It was a time that’s hard to imagine for the modern westerner when one of the greatest health threats facing the impoverished in America is obesity! In Hong Kong at that time, the people were literally starving to death. Please keep that in mind when you see old photos of that era.

At any rate, we can understand the toughness of a people who’ve survived such a war and such horrific deprivations. And it was to these survivors – men like Wong Shun Leung – that Ip Man broke from tradition and told to go test the stuff to see if it worked.

Which brings us to the second reason that Lee moved toward boxing in his later years.

Quite simply, in America, which had been, by comparison, untouched by the ravages of war, and was awash in material wealth, there wasn’t a culture of “trying things out” in the martial community like there had been back in Hong Kong. But driven by the philosophy of Ip Man, that being that a theory had to work in practice, Lee was hell-bent on practicality. Boxing offered this to him. It gave him the ability to test things out and, not only that, but a rich history of adaptation and change. In short, to Lee’s mind, boxing was the logical extension or, perhaps more accurately, the martial sibling to his foundation art of Wing Chun.

The proof of this is a letter that he sent to his senior and mentor in Wing Chun, Wong Shun Leung. Here’s the letter:

“Dear Shun-Leung, Jan. 11, 1970

“It has been a long time since I last wrote to you. How are you? Alan Shaw’s letter from Canada asks me to lend you my 8mm film. I’m sorry about that. It is because I have lost it when I moved my home. That film is already very old and I seldom use it, so I have lost it. I am sorry for it.

“Now I have bought a home in Bel-Air. It is about half an acre. There are many trees. It has the taste of a range. It is located on a hilltop near Beverly Hills. Moreover, besides my son Brandon, I have had a daughter, Shannon, who is seven months old now. Have you re-married? Please send my regard to your sisters. Recently, I have organized a film company. I have also written a story ‘The Silent Flute’. James Coburn and I will act in it. Stirling Silliphant is the screen-play writer. He is a famous screen-play writer (In the Heat of the Night). We plan to make the first fighting film in Hollywood. The prospect is good. About six months later, the filming work will begin. All who participate in this film are my followers. In the future, Steve McQueen may also work together with me.

“I am very excited about this plan. As to martial arts, I still practice daily. I meet my students and friends twice a week. No matter they are western boxer, Tae Kwon Do learner or wrestler, I will meet them as long as they are friendly and will not get angry.

“Since I started to practice realistically in 1966 (Protectors, gloves, etc.), I feel that I had many prejudices before, and they are wrong. So I change the name of the gist of my study to Jeet-kune-do. Jeet-kune-do is only a name. The most important thing is to avoid having bias in the training. Of course, I run everyday, I practice my instruments (punch, kick, throw, etc.). I have to raise the basic conditions daily.

“Although the principle of boxing is important, practicality is even more important. I thank you and Master for teaching me the ways of Wing Chun in Hong Kong. Actually, I have to thank you for leading me to walk on a practical road. Especially in the States, there are western boxers, I often practice with them too. There are many so-called masters in Wing Chun here, I really hope that they will not be so blind to fight with those western boxers may make a trip to Hong Kong. I hope that you will live in the same place.

“We are intimate friends, we need to meet more and chat about our past days. That will be a lot of fun? When you see Master Yip, please send my regard to him. Happiness be with you!

“Bruce Lee.”

When we couple this letter with the fact that Lee’s Tao of Jeet Kune Do, published posthumously and originally intended to be a manual for his personal students, was actually copied itself from old boxing and fencing manuals, we have settled the issue of JKD’s origins. Our contention that Lee’s JKD followed the principles of boxing and that he owed this to his instruction in Wing Chun from Ip Man isn’t speculation but, rather, the direct words and deeds of the man himself. In the famed Tao, often seen as evidence of Lee’s martial genius, he literally copied dozens of pages from old boxing and fencing manuals. Modern boxing had grown out of the fencing era, relying on straight hits, footwork, timing and deception. So, indeed, he was a genius but a different one than most of us are led to believe.

The infighting presented in this book, therefore, will have a greater streak of boxing running through it than the JKD Foundations book. At long range, JKD can resemble fencing a bit more but that’s all gone when you are fighting in the trenches. A thing to note, of course, is Lee’s own words in the letter to his mentor. He says that though boxing principles are important, practicality and realism are the key. What this means is that Lee built his JKD on the well vetted and tested principles of boxing. Modifications made for street-fighting – such as takedown defense, head-butting, eye jabs, low blows, etc. – while necessary and extremely helpful in the cause of personal defense, are still in orbit around the boxing principles. Those principles are what Lee liked to call aliveness. In particular, they’re evasion, powerful striking from any angle, and mobility.

If you were so inclined to say that JKD is simply boxing then, we would disagree. There’s a difference in building on the foundation of a thing and being that thing. A boxer can cheat but he would have to make a conscious effort to override his muscle and tactical memory in order to do so. The JKD approach is a scientific “cheating” – a highly organized, yet simple adaptation of the boxing methodology in order to help keep the self-defender as safe as possible in the event of a sudden and violent encounter. Thus, JKD is like boxing but isn’t boxing. On the other hand, those JKD variants that are less like boxing and more like something else – like say, Kali – are less like JKD too. To jettison the boxing roots of JKD – especially on the inside – is to cut oneself off from the scientific nature of the combat.

To prove my point, I’d like to offer this example.

Back in 1996 my school was very small. I had a 400 square foot place on Wade Hampton Boulevard in Taylors, South Carolina. (Talk about humble beginnings…the Lord has blessed my work mightily!). One evening a guy came in and asked why I wasn’t teaching BJJ. He went on to explain that unless I was teaching Gracie style BJJ that I’d be out of business in short order. The strength of his argument rested upon the small sample-size evidence of the recent UFC matches in which Royce Gracie was dominant.

Well, to this I replied that boxing was still the king in any universe where people throw punches at each other. As soon as the fighters adapted their tactics to account for BJJ – that is, learned to sprawl and punch properly, you’d see a radical reordering of the UFC. He laughed derisively at that and shook his head in a way a man shakes his head when someone tells him he was once abducted by aliens. Or that 9/11 was an inside job. Or that you can trust Congress.

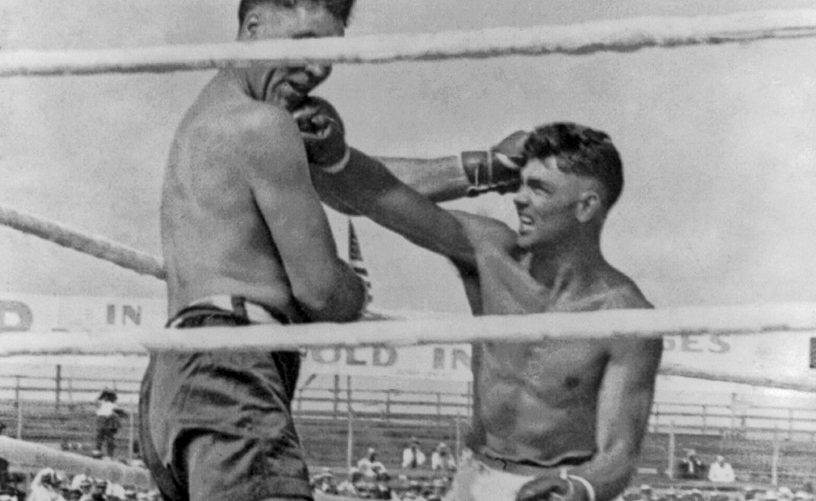

Anyway, here we are over 20 years later and we know that a UFC fighter without boxing is an accident waiting to happen.

We must add, though, that the old-school boxing we present – and that being Jack Dempsey style predominantly – is better suited for all-out fighting than MMA. This is due to the variables like asphalt rather than mats, headbutts, eye, throat and groin strikes, multiple opponents and so on. We’ll cover all this in more detail as we go but we remember that Lee’s goal was realism and that he once remarked that boxing was “over-daring” due to its reliance on rules. It was his belief that a martial artist was training for war, not sport and that sport, while extremely helpful in regard to testing certain aspects of one’s game, if left unchecked, would dominate one’s understanding of self-defense and thus weaken it. We remind the reader that if you aren’t cheating in combat you aren’t trying to win insofar as we define cheating as the use of tactics and targets that are the most difficult to defend.

In closing, if you think that Dempsey or Tyson were destructive, and they certainly were, then you need to understand how and why that was the case. That’s what made Lee such an outstanding thinker. He saw people getting the results he wanted and began his research there. JKD infighting is, therefore, the extrapolations of close-quarter boxing applied to street-defense – all-out, life-or-death combat.